Edward Alexander MacDowell (1860-1908) [biography]

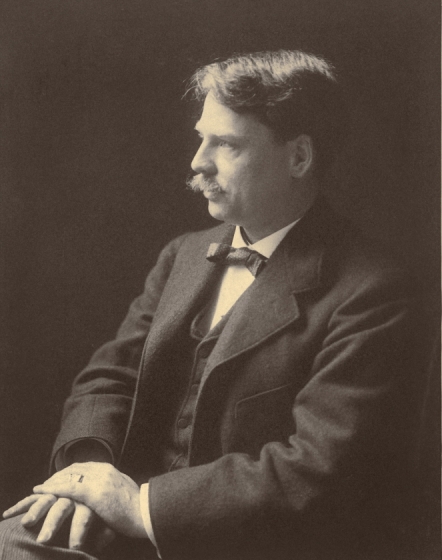

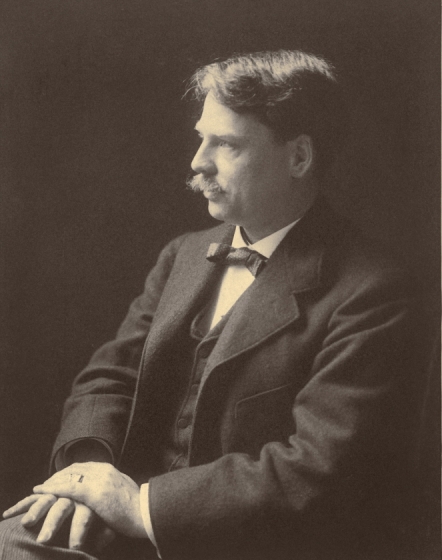

Edward Alexander MacDowell, head-and-shoulders portrait, seated, facing right, between 1890 and 1908. Prints and Photographs Reading Room, Library of Congress.

Edward MacDowell was one of the most celebrated American composers in the nineteenth century. His compositions won the approval of music critics, both in Europe and the United States, as well as of his contemporaries, including composers such as Franz Liszt and Joachim Raff. MacDowell's early works bear the influence of his training in Germany, reflecting European styles and cultures. Nearly all of his compositions feature descriptive titles, a trend representative of Romantic music. He was among the first seven Americans honored by membership in the American Academy of Arts and Letters (1904).

While there has been controversy in determining his birth year, recent evidence suggests that MacDowell was born in New York City on 18 December 1860. The son of Thomas MacDowell and Frances "Fanny" Knapp MacDowell, the youth grew up in a Quaker household on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Frances MacDowell firmly believed that Edward should have music lessons, so she arranged for her eight-year old son to take piano lessons from Colombian violinist Juan Buitrago. MacDowell soon surpassed Buitrago's abilities and began studying piano with Cuban pianist Pablo Desverine. Desverine's lessons were supplemented by sessions with Venezuelan pianist Teresa Carreño, who later championed MacDowell's works.

In 1876, at the age of fifteen, MacDowell, accompanied by his mother, traveled to France to enroll in the Paris Conservatoire. He earned one of the conservatoire's scholarships awarded to foreign students and gained admission to Antoine François Marmontel's studio. Marmontel was one of the most sought-after piano teachers of the time, and he accepted only thirteen students, including MacDowell, out of 230 applicants. After only two years, MacDowell grew dissatisfied with the instruction at the conservatoire and moved to Germany to continue his education.

In the fall of 1879, MacDowell entered the Frankfurt Conservatory, where he studied piano with Carl Heymann and composition with Joachim Raff. It was during this time that MacDowell became acquainted with Franz Liszt. Upon visiting Raff's class in early 1880, Liszt heard MacDowell play the piano part of Robert Schumann's Quintet, op. 44 (Schumann's widow, Clara, was also present at that performance). The following year, MacDowell visited Liszt in Weimar and played his own Piano Concerto in A Minor, op. 15, for the maestro. On Liszt's recommendation, MacDowell's First Modern Suite, op. 10, was performed on 11 July 1882 at the Allgemeine deutsche Musikverein; Liszt also encouraged the prestigious Leipzig firm of Breitkopf & Härtel to publish the work.

After Heymann's retirement in 1881, MacDowell began his professional career as a teacher at the Darmstadt Conservatory. He resigned a year later, but continued to teach privately. He fell in love with one of his students, Marian Nevins, whom he secretly married on 11 July 1884 (a public ceremony followed on 21 July). The couple lived in Germany for several years, during which time MacDowell dedicated himself solely to composition. He achieved fame with his Piano Concerto in A Minor, op. 15, which was championed by Carreño, and his Fantasy Pieces, op. 17.

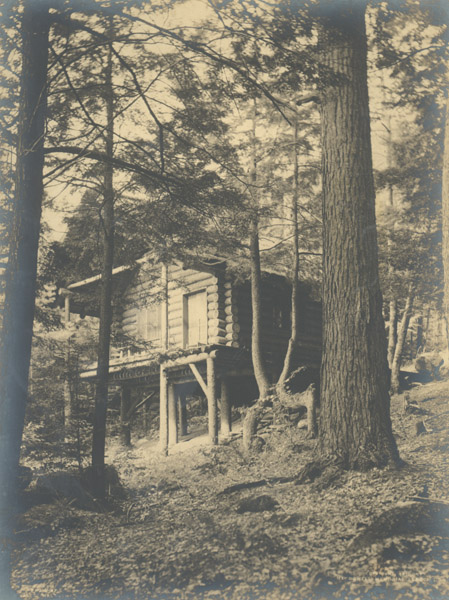

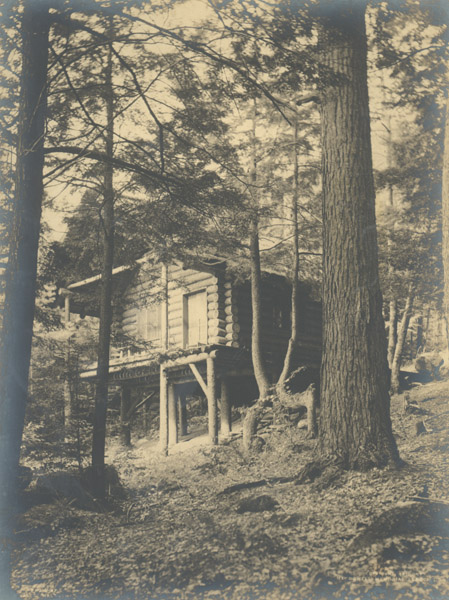

Financial difficulties forced the MacDowells to return to America in 1888, and for nearly ten years they resided in Boston. Among the compositions penned by MacDowell during this period was his Indian Suite, op. 48 (1896), for orchestra, one of his most famous works. In 1896 the MacDowells purchased land in New Hampshire, and in a cabin built on this property, Edward composed his Woodland Sketches, op. 51 (1896), for piano. The natural surroundings of this New Hampshire retreat would ultimately inspire generations of composers, for it was in this location in 1907 that the MacDowell Colony was established. The colony, a sanctuary for composers, painters, authors, and sculptors, continues to sponsor and support artists to this day.

MacDowell joined the faculty of Columbia University in 1896. As the sole music professor at the university for nearly two years, MacDowell also served as the department's administrator. In addition to teaching, he directed the Mendelssohn Glee Club (New York). He also started an all-male chorus at Columbia University in order to raise artistic standards of college glee clubs and music societies.

MacDowell's compositions include two piano concertos, two orchestral suites, four symphonic poems, four piano sonatas, piano suites, forty-two songs, and choral music, most of which is for male voices. He also published dozens of piano transcriptions of eighteenth-century pre-piano keyboard pieces.

MacDowell wrote a great deal of solo song repertoire between 1880 and 1901. Early songs were on German texts by Heine, Klopstock, and Goethe; later he set texts by Shakespeare, Burns, Gardner, and Howells, as well as his own poetry. For the Mendelssohn Glee Club, he wrote nine arrangements for male voices of works by Borodin, Sokolov, Rimsky-Korsakov, and others, which the Club premiered. He also arranged and composed college songs for Columbia University's men's glee club.

From 1896 to 1898, MacDowell published four part songs for the Mendelssohn Glee Club under the pseudonym of Edgar Thorn. Since MacDowell conducted the group, he feared members would feel obligated to accept his compositions if he revealed he had written them. MacDowell also wrote nine other works under his own name. Eight of his works were premiered by the Mendelssohn Glee Club under his direction between 1897 and 1898.

In 1904, after serious disputes with Murray Butler (the new president of Columbia) regarding the role of the university's music program, MacDowell resigned from the post. As a result of the trauma associated with the much-publicized event at Columbia, an accident with a hansom cab, and his depression and general declining health, MacDowell's condition rapidly deteriorated, and he died on 23 January 1908. Marian MacDowell, however, survived her husband by nearly five decades, spending the majority of her remaining years tending to the MacDowell Colony's operations. After Marian's death in 1956, her estate sold MacDowell's materials to the Library of Congress in 1972, allowing researchers and scholars access to the holograph manuscripts, correspondence, and personal papers of one of America's most prominent composers.

Further Reading:

Levy, Alan H. Edward MacDowell: An American Master. Lanham, Maryland, and London: Scarecrow Press, 1998.

MacDowell, Marian. Random Notes on Edward MacDowell and his Music. Boston: Arthur P. Schmidt and Co., 1950.

Last Updated: 08-26-2011

Fuente: http://lcweb2.loc.gov/diglib/ihas/loc.natlib.ihas.200035715/default.html

MacDowell Colony

History

In 1896, Edward MacDowell, a composer, and Marian MacDowell, a pianist, bought a farm in Peterborough, New Hampshire, where they spent summers working in peaceful surroundings. It was in Peterborough that Edward, arguably America’s first great composer, said he produced more and better music. Not long after — falling prematurely and gravely ill — Edward conveyed to his wife that he wished to give other artists the same creative experience under which he had thrived.

Before his death in 1908, Marian set about fulfilling his wish of making a community on their New Hampshire property where artists could work in an ideal place in the stimulating company of peers. Their vision became nationally known as the “Peterborough Idea,” and in 1906, prominent citizens of the time — among them Grover Cleveland, Andrew Carnegie, and J. Pierpont Morgan — created a fund in Edward’s honor to make the idea a reality. Although Edward lived to see the first Fellows arrive, it was under Marian’s leadership that support for the Colony increased, most of the 32 studios were built, and the artistic program grew and flourished. Until her death in 1956, she traveled across the country to further public awareness about the Colony’s mission, giving lecture-recitals to raise funds for its preservation.

At its founding, the Colony was an experiment with no precedent. It stands now having provided crucial time and space to more than 6,000 artists, including such notable names asLeonard Bernstein, Thornton Wilder, Aaron Copland, Milton Avery, James Baldwin, Spalding Gray, and more recently Alice Walker, Alice Sebold, Jonathan Franzen, Michael Chabon, Suzan-Lori Parks, Meredith Monk, and many more.

In 1997, The MacDowell Colony was honored with the National Medal of Arts — the highest award given by the United States to artists or arts patrons — for “nurturing and inspiring many of this century’s finest artists” and offering them “the opportunity to work within a dynamic community of their peers, where creative excellence is the standard.” In 2007, the Colony celebrated its

Centennial with a yearlong celebration of the freedom to create. You can browse through MacDowell's history by viewing the

Centennial timeline here.

Marian MacDowell at the Log Cabin, the studio she built for her husband, composer Edward MacDowell. Photo credit: Archival image.

Marian MacDowell in front of Edward's log cabin, the Colony's prototype studio. Archival image.

The "House of Dreams Untold"—the log cabin in the woods at Peterboro where MacDowell composed, and where most of his later music was written

http://lcweb2.loc.gov/diglib/ihas/loc.natlib.ihas.200035715/default.html

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/14109/14109-h/14109-h.htm

http://www.macdowellcolony.org/about.html

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario