Nicholas Carr

Nicholas Carr estudió Literatura en Dartmouth College y en la Universidad de Harvard y todo indica que fue en su juventud un voraz lector de buenos libros. Luego, como le ocurrió a toda su generación, descubrió el ordenador, el Internet, los prodigios de la gran revolución informática de nuestro tiempo, y no sólo dedicó buena parte de su vida a valerse de todos los servicios online y a navegar mañana y tarde por la Red; además, se hizo un profesional y un experto en las nuevas tecnologías de la comunicación sobre las que ha escrito extensamente en prestigiosas publicaciones de Estados Unidos e Inglaterra.

Un buen día descubrió que había dejado de ser un buen lector, y, casi casi, un lector. Su concentración se disipaba luego de una o dos páginas de un libro, y, sobre todo si aquello que leía era complejo y demandaba mucha atención y reflexión, surgía en su mente algo así como un recóndito rechazo a continuar con aquel empeño intelectual. Así lo cuenta: “Pierdo el sosiego y el hilo, empiezo a pensar qué otra cosa hacer. Me siento como si estuviese siempre arrastrando mi cerebro descentrado de vuelta al texto. La lectura profunda que solía venir naturalmente se ha convertido en un esfuerzo”.

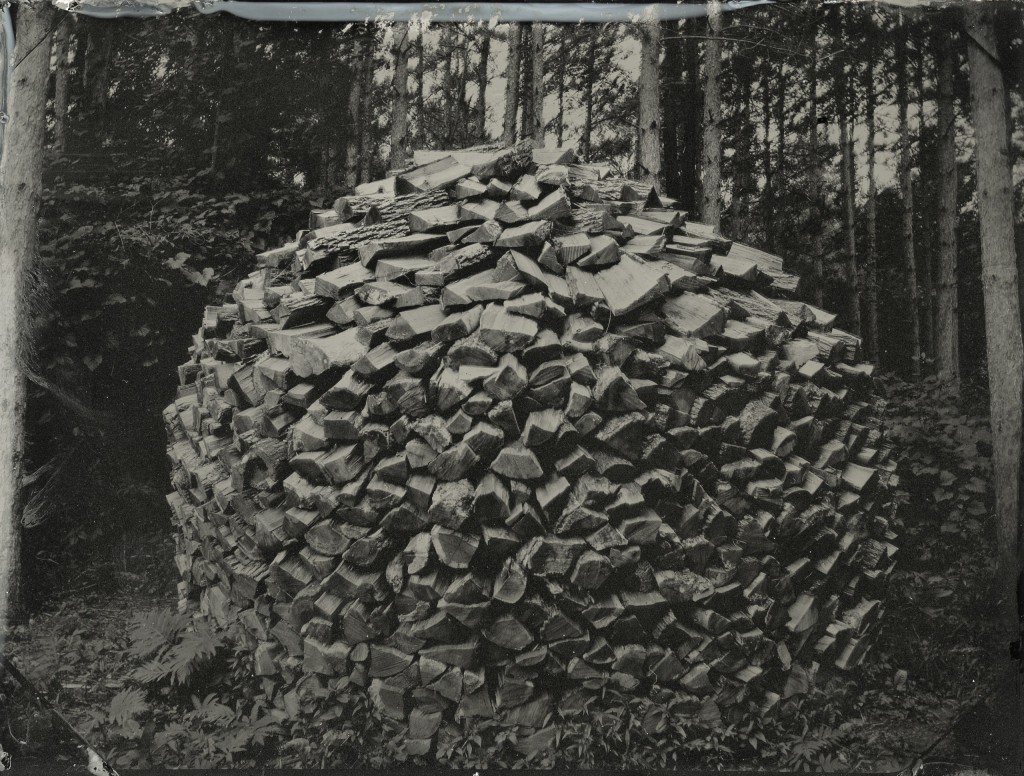

Preocupado, tomó una decisión radical. A finales de 2007, él y su esposa abandonaron sus ultramodernas instalaciones de Boston y se fueron a vivir a una cabaña de las montañas de Colorado, donde no había telefonía móvil y el Internet llegaba tarde, mal y nunca. Allí, a lo largo de dos años, escribió el polémico libro que lo ha hecho famoso. Se titula en inglés The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains y, en español, Superficiales: ¿Qué está haciendo Internet con nuestras mentes? (Taurus, 2011). Lo acabo de leer, de un tirón, y he quedado fascinado, asustado y entristecido.

Carr no es un renegado de la informática, no se ha vuelto un ludita contemporáneo que quisiera acabar con todas las computadoras, ni mucho menos. En su libro reconoce la extraordinaria aportación que servicios como el de Google, Twitter, Facebook o Skype prestan a la información y a la comunicación, el tiempo que ahorran, la facilidad con que una inmensa cantidad de seres humanos pueden compartir experiencias, los beneficios que todo esto acarrea a las empresas, a la investigación científica y al desarrollo económico de las naciones.

Pero todo esto tiene un precio y, en última instancia, significará una transformación tan grande en nuestra vida cultural y en la manera de operar del cerebro humano como lo fue el descubrimiento de la imprenta por Johannes Gutenberg en el siglo XV que generalizó la lectura de libros, hasta entonces confinada en una minoría insignificante de clérigos, intelectuales y aristócratas. El libro de Carr es una reivindicación de las teorías del ahora olvidado Marshall MacLuhan, a quien nadie hizo mucho caso cuando, hace más de medio siglo, aseguró que los medios no son nunca meros vehículos de un contenido, que ejercen una solapada influencia sobre éste, y que, a largo plazo, modifican nuestra manera de pensar y de actuar. MacLuhan se refería sobre todo a la televisión, pero la argumentación del libro de Carr, y los abundantes experimentos y testimonios que cita en su apoyo, indican que semejante tesis alcanza una extraordinaria actualidad relacionada con el mundo del Internet.

Los defensores recalcitrantes del software alegan que se trata de una herramienta y que está al servicio de quien la usa y, desde luego, hay abundantes experimentos que parecen corroborarlo, siempre y cuando estas pruebas se efectúen en el campo de acción en el que los beneficios de aquella tecnología son indiscutibles: ¿quién podría negar que es un avance casi milagroso que, ahora, en pocos segundos, haciendo un pequeño clic con el ratón, un internauta recabe una información que hace pocos años le exigía semanas o meses de consultas en bibliotecas y a especialistas? Pero también hay pruebas concluyentes de que, cuando la memoria de una persona deja de ejercitarse porque para ello cuenta con el archivo infinito que pone a su alcance un ordenador, se entumece y debilita como los músculos que dejan de usarse.

No es verdad que el Internet sea sólo una herramienta. Es un utensilio que pasa a ser una prolongación de nuestro propio cuerpo, de nuestro propio cerebro, el que, también, de una manera discreta, se va adaptando poco a poco a ese nuevo sistema de informarse y de pensar, renunciando poco a poco a las funciones que este sistema hace por él y, a veces, mejor que él. No es una metáfora poética decir que la “inteligencia artificial” que está a su servicio, soborna y sensualiza a nuestros órganos pensantes, los que se van volviendo, de manera paulatina, dependientes de aquellas herramientas, y, por fin, en sus esclavos. ¿Para qué mantener fresca y activa la memoria si toda ella está almacenada en algo que un programador de sistemas ha llamado “la mejor y más grande biblioteca del mundo”? ¿Y para qué aguzar la atención si pulsando las teclas adecuadas los recuerdos que necesito vienen a mí, resucitados por esas diligentes máquinas?

No es extraño, por eso, que algunos fanáticos de la Web, como el profesor Joe O’Shea, filósofo de la Universidad de Florida, afirme: “Sentarse y leer un libro de cabo a rabo no tiene sentido. No es un buen uso de mi tiempo, ya que puedo tener toda la información que quiera con mayor rapidez a través de la Web. Cuando uno se vuelve un cazador experimentado en Internet, los libros son superfluos”. Lo atroz de esta frase no es la afirmación final, sino que el filósofo de marras crea que uno lee libros sólo para “informarse”. Es uno de los estragos que puede causar la adicción frenética a la pantallita. De ahí, la patética confesión de la doctora Katherine Hayles, profesora de Literatura de la Universidad de Duke: “Ya no puedo conseguir que mis alumnos lean libros enteros”.

Esos alumnos no tienen la culpa de ser ahora incapaces de leer Guerra y Paz o El Quijote. Acostumbrados a picotear información en sus computadoras, sin tener necesidad de hacer prolongados esfuerzos de concentración, han ido perdiendo el hábito y hasta la facultad de hacerlo, y han sido condicionados para contentarse con ese mariposeo cognitivo a que los acostumbra la Red, con sus infinitas conexiones y saltos hacia añadidos y complementos, de modo que han quedado en cierta forma vacunados contra el tipo de atención, reflexión, paciencia y prolongado abandono a aquello que se lee, y que es la única manera de leer, gozando, la gran literatura. Pero no creo que sea sólo la literatura a la que el Internet vuelve superflua: toda obra de creación gratuita, no subordinada a la utilización pragmática, queda fuera del tipo de conocimiento y cultura que propicia la Web. Sin duda que ésta almacenará con facilidad a Proust, Homero, Popper y Platón, pero difícilmente sus obras tendrán muchos lectores. ¿Para qué tomarse el trabajo de leerlas si en Google puedo encontrar síntesis sencillas, claras y amenas de lo que inventaron en esos farragosos librotes que leían los lectores prehistóricos?

La revolución de la información está lejos de haber concluido. Por el contrario, en este dominio cada día surgen nuevas posibilidades, logros, y lo imposible retrocede velozmente. ¿Debemos alegrarnos? Si el género de cultura que está reemplazando a la antigua nos parece un progreso, sin duda sí. Pero debemos inquietarnos si ese progreso significa aquello que un erudito estudioso de los efectos del Internet en nuestro cerebro y en nuestras costumbres, Van Nimwegen, dedujo luego de uno de sus experimentos: que confiar a los ordenadores la solución de todos los problemas cognitivos reduce “la capacidad de nuestros cerebros para construir estructuras estables de conocimientos”. En otras palabras: cuanto más inteligente sea nuestro ordenador, más tontos seremos.

Tal vez haya exageraciones en el libro de Nicholas Carr, como ocurre siempre con los argumentos que defienden tesis controvertidas. Yo carezco de los conocimientos neurológicos y de informática para juzgar hasta qué punto son confiables las pruebas y experimentos científicos que describe en su libro. Pero éste me da la impresión de ser riguroso y sensato, un llamado de atención que -para qué engañarnos- no será escuchado. Lo que significa, si él tiene razón, que la robotización de una humanidad organizada en función de la “inteligencia artificial” es imparable. A menos, claro, que un cataclismo nuclear, por obra de un accidente o una acción terrorista, nos regrese a las cavernas. Habría que empezar de nuevo, entonces, y a ver si esta segunda vez lo hacemos mejor.

MARIO VARGAS LLOSA

© Derechos mundiales de prensa en todas las lenguas reservados a Ediciones EL PAÍS, SL, 2011. © Mario Vargas Llosa, 2011.

http://www.economiapersonal.com.ar/2011/08/06/mas-informacion-menos-conocimiento/

http://www.abc.es/20110301/medios-redes/abci-nicholas-carr-201102281759.html