|

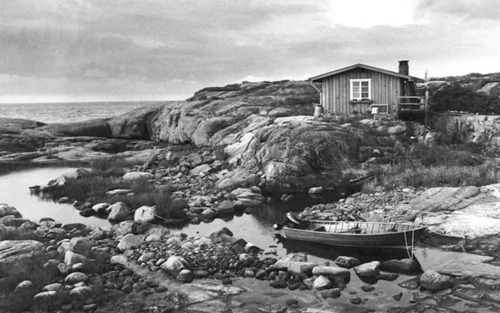

Bill Starling for The New York Times

Sonny Brewer in the hut that inspired

his first novel, "The Poet of Tolstoy Park." |

Today, Mr. Stuart's hut in Fairhope has become an odd sort of tourist attraction, a kind of temple to eccentricity and individualism, thanks largely to another Fairhope eccentric, a goateed man often seen in a seersucker suit riding around town on a Harley-Davidson: the novelist Sonny Brewer.

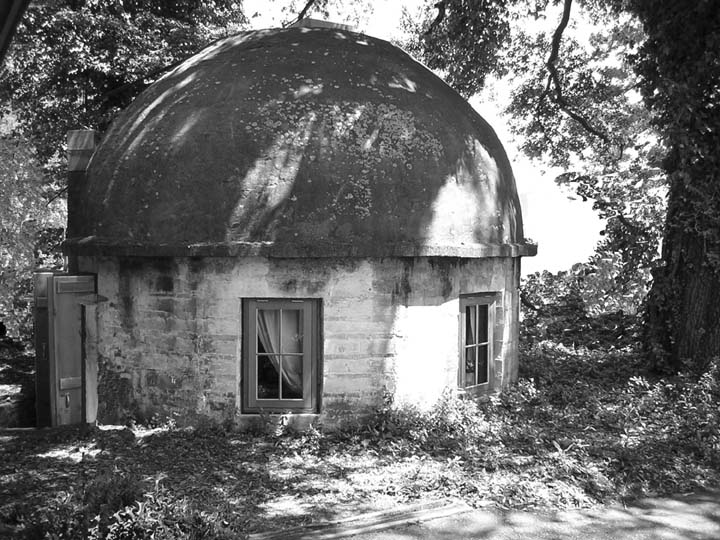

Since the publication last year of Mr. Brewer's first novel, "The Poet of Tolstoy Park" (Ballantine), which is based on Mr. Stuart's life and the construction of his concrete hut, readers, along with various searchers, spiritualists and philosophical types, have been turning up at the hut to commune with Mr. Stuart. Two thousand people have signed a guest book Mr. Brewer left in the hut last year, and some have brought sleeping bags and spent the night inside.

"It's a special place," said Jimbo Meador, 64, a kayak designer who lives in nearby Point Clear and who meditates regularly in the hut. "The acoustics in there are pretty unusual. Like you say, 'Om,' and it really resonates."

Mr. Brewer, who is 57, is quick to cop to the charge of being an oddball, even by Fairhope standards. He has been a carpenter, a bookstore owner, a real estate agent, an editor and a rock musician, and he once sold vintage cars for a living, though he lost money at it.

Mr. Brewer has also been through a boat phase, an R.V. phase, a convertible phase, and several motorcycle phases. As for religions, he's tried a bunch of those, too: He was raised a Baptist, became a Methodist, a Presbyterian, a Quaker, and converted to Catholicism for a while. Mr. Brewer said he's an Episcopalian — for now.

"I sometimes have a feeling I'm from another planet," Mr. Brewer said in a soft southern Alabama drawl. "Even my own behavior looks alien and ridiculous to me."

Mr. Brewer discovered Henry Stuart's hut in the 1980's during one of those career changes. He had quit his job as a carpenter, and was on his way to a seminar on selling real estate when he pulled into a parking lot about a mile from town. Though originally built on 10 acres of wilderness, the hut in the intervening years had been encroached upon as Fairhope grew. Office buildings have been built to within six feet of the dwelling. It now sits just off the parking lot of a local Coldwell Banker office, which used the hut for years to store its "for sale" signs.

"I thought, 'What is this crazy little house doing in a parking lot?' " Mr. Brewer recalled. "It was like finding a very strange bird nest in the forest. You want to know, 'What kind of bird built this?' "

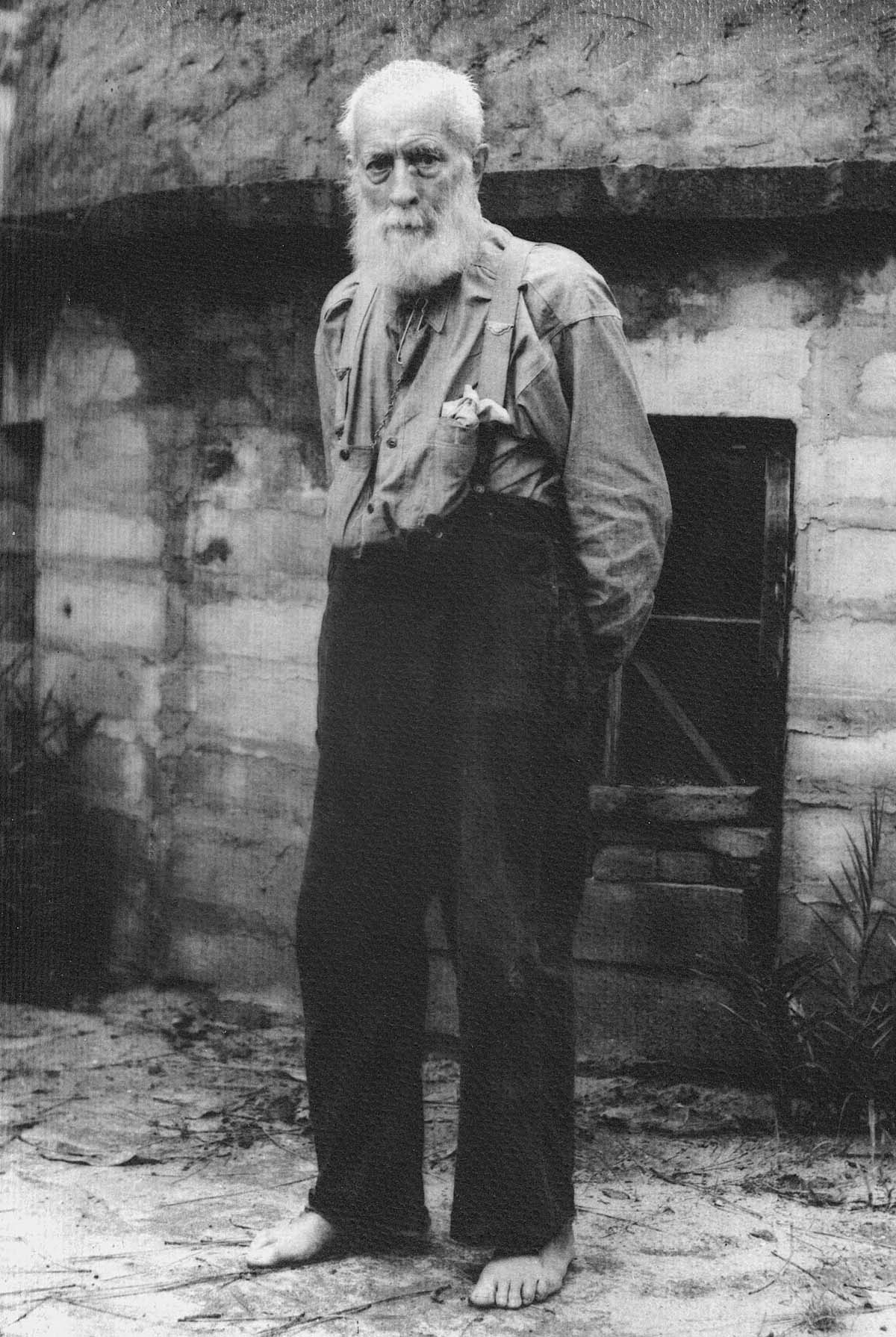

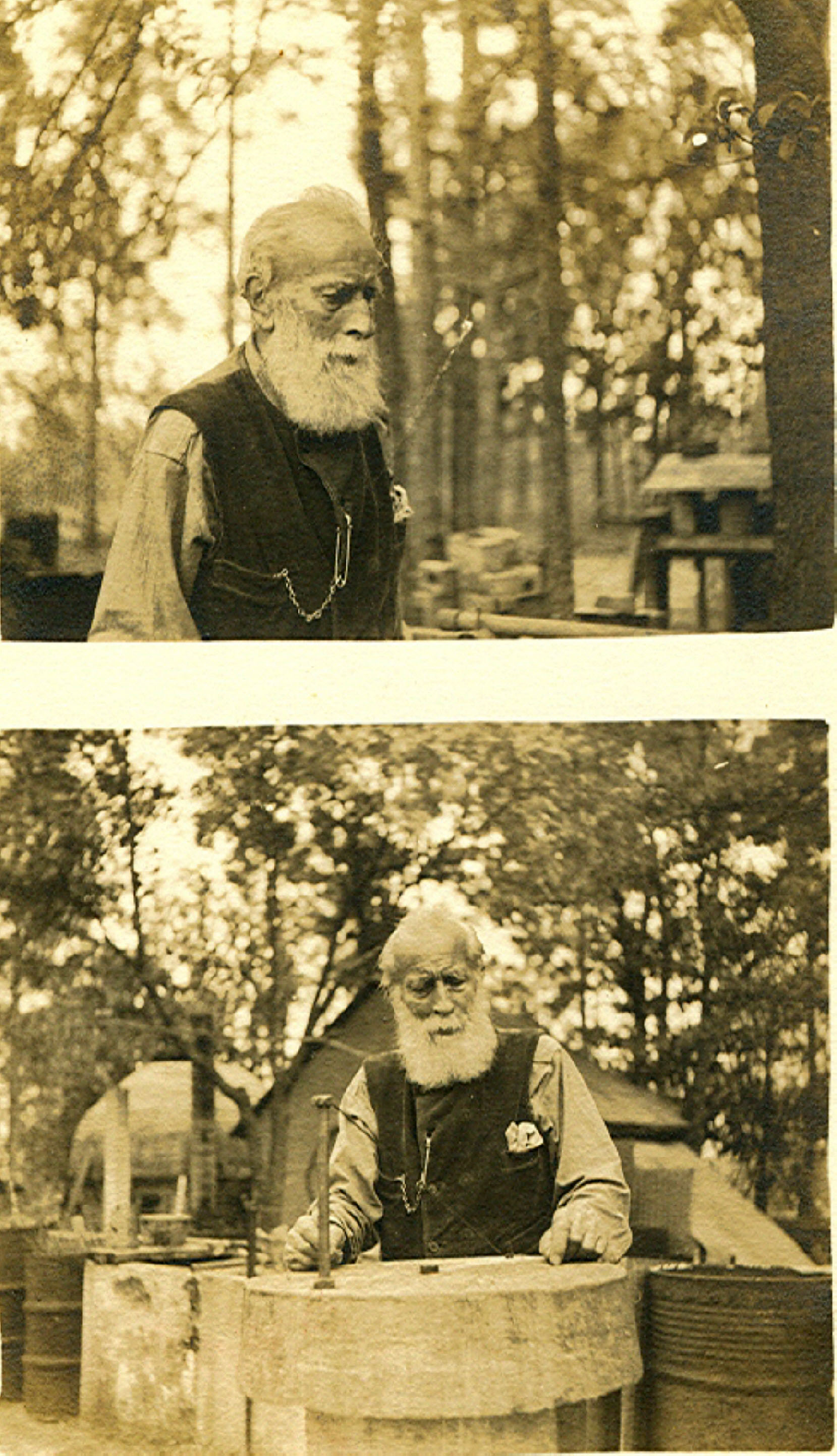

Inside the real estate office, Mr. Brewer came across a framed copy of a newspaper article about Mr. Stuart and his hut. Mr. Stuart, the article said, left behind two grown sons in Idaho when he came South to die. He admired Tolstoy, naming the acreage around the hut Tolstoy Park, and with his white beard even resembled him.

Mr. Stuart was described as quick to lend a dollar, and unconcerned about repayment. And though described as a hermit, he accepted visitors regularly; 1,200 people signed a guest book he kept in his hut, according to one article, including the lawyer Clarence Darrow.

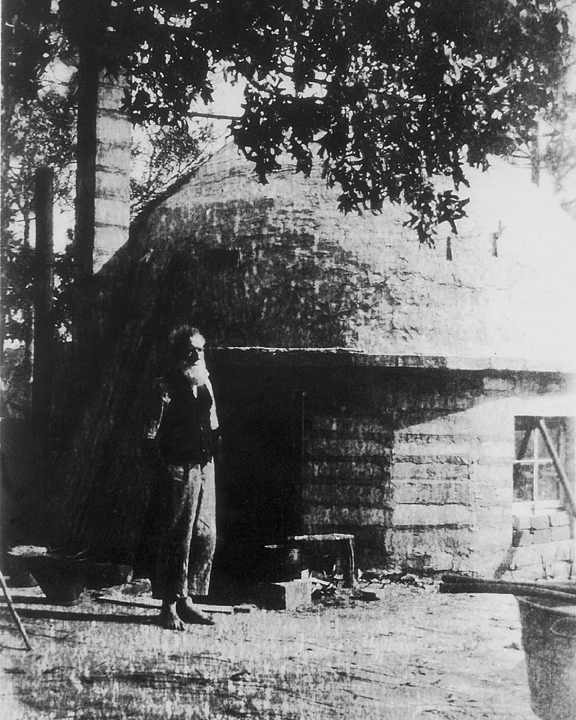

Mr. Stuart, who was in his late 60's at the time, built his hut over the course of a year and 16 days in 1925 and 1926, and refused all help with the construction, the newspaper reported. Mr. Stuart's bed was a hammock that hung 10 feet off the ground; he could get in only by climbing a ladder. He kept a loom on the floor that he used to weave rugs, which he sold for a living.

"I was completely mesmerized," Mr. Brewer said.

He managed to find two other newspaper articles about Mr. Stuart, and six photographs. Mr. Stuart is barefoot in all of them, even one taken with a woman in a winter coat.

The more Mr. Brewer learned about the man, he said, the more obsessed he became.

"I identified with Henry; he did what he wanted to do, and so did I," Mr. Brewer said.

He decided to try to write about Henry Stuart. He considered a nonfiction account of Mr. Stuart's life, but settled on fiction, "because I lie," he said. He wrote a couple of short stories about Mr. Stuart, and the first 20 pages of a novel, but put it aside in favor of an autobiographical novel about his own life, which he sent to a literary agent in San Francisco.

By now, Mr. Brewer had quit real estate to open an independent bookstore called Over the Transom, in Fairhope. It was losing money — a lot of money. Mr. Brewer's only hope was that his novel would sell, but his agent was not optimistic and asked him if he had anything else. Mr. Brewer mentioned the Stuart novel, which begins with Mr. Stuart taking off his shoes after hearing the news that he will die. Based on the first 20 pages and a six-page outline, the agent sold the novel to Ballantine for $100,000.

Mr. Brewer said he got the news hours before an appointment with a bankruptcy lawyer.

"I broke down and cried," he said.

Mr. Brewer's next move was to persuade a local banker who owns the hut and the land around it to rent the building to him for $9 a month. He wrote a draft of "The Poet of Tolstoy Park" in four fevered months, and then immediately set about restoring the hut, ridding it of "snakes and lizards and fast-food wrappers," he said, replacing windows and removing a wooden floor. When he was finished, he moved in to revise his novel — while barefoot.

"Where did Henry Stuart stop and Sonny Brewer start?" Mr. Brewer asked. "That line was not clear. Some ladies from the real estate office told me they thought I had gone crazy."

A local architect who studied the hut noticed that the diameter of the floor, 14 feet, perfectly matched the distance between the floor and the top of the hut's domed roof. The hut was also dug 16 inches into the ground, which at that depth is a constant 57 degrees, making the floor cool in the summer and warm in the winter.

When he was finished with his book, Mr. Brewer left a copy of the manuscript in the hut, and then left the door unlocked. Shortly after publication last year, he began to hear from people who had visited.

One of those people was Wilson McDuff, 35, a schoolteacher from Fairhope who spent a night in the hut last year with his father and son. "It was kind of weird to me," Mr. McDuff said. "I started imagining what it would be like to be Henry Stuart, living in a little bitty house like that. I was inspired."

Mr. McDuff's father died later that year in a cycling accident. Unable to sleep the night he heard the news, Mr. McDuff said he was drawn back to the hut. "I didn't feel like I was alone anymore," he said. "It was comforting to think about Henry Stuart and to know that just because you're not here doesn't mean you're forgotten."

Somewhere along the way, Mr. Brewer said, people began leaving coins and dollar bills in an iron skillet in the hut, money that seems to be lent and borrowed according to Mr. Stuart's principles.

"Sometimes I come in here and it's $65, sometimes it's $5," Mr. Brewer said with a shrug. "The pile just comes and goes."

Mr. Brewer said that so far he has remained on good terms with the banker who owns the hut. But one thought keeps him up at night.

"My fear is that sooner or later the proverbial offer that can't be refused might come along," he added. "I could see a Blockbuster Video standing where Henry's house is."

That thought has inspired Mr. Brewer's latest crusade: getting the hut placed on the National Register of Historic Places, a move that could help preserve it in perpetuity. So far it hasn't gone so well. Though the State of Alabama designated the hut a landmark, the United States Department of the Interior said that his application needed more work.

"They said it was too weird," Mr. Brewer said.